To understand what Brisbane was like in the 1980s, understand that I once paid the equivalent of nearly $750 to score a beer on a Sunday. In those days, pubs could open on Sunday for only two hours at lunch and two more in the evening. If you found yourself in possession of an intolerable thirst outside of those times, you had but one option. The bar at the airport.

Brisbane Airport was then a small sanctuary from the predations of local punishers and straighteners, its precious freedoms and generous serving hours vouchsafed by the Commonwealth Government. My flatmate Pete and I, in need of beers one long dry Sunday, fetched up there. Some forgotten number of schooners—actual schooners!—later, dizzy with the heady taste of freedom and froths that were not Fourex, we talked ourselves into catching a standby flight to Sydney just to have a drink in their airport bar too.

It was a hell of a place, Brisbane in the Before Times. Corrupt, backward and oppressive in a way that had nothing to do with the steam press humidity. It pushed down on you at all times, the sense of what was possible being crushed, slowly, between hamfisted political coercion and cultural suffocation.

And yet, the underground music scene was kicking. A strange and contrary school of writers emerged. Unearthly subcultures took root in a fertile mulch fed by rot and genesis.

The boss-level culture, the dominant paradigm, was hugely dominant. It was white, masculine, possessive, and dangerous, really dangerous if you crossed it. But mostly, it was just dumb and self-satisfied. I remember being knocked back at the door of a beer garden with my Super Goth girlfriend because she too was way too Goth, and my shoes weren’t, I don’t know, ‘boaty’ enough or something. I remember looking in on the debauched blood-house frenzy inside and thinking, “Seriously? We’re the problem here?”

But it didn’t matter because we didn’t fit in. They sent us away.

They sent a lot of people away in those days. A constant refugee flow of the city’s youth headed for Sydney and Melbourne or calling in for a final airport beer before lighting out overseas. Most declared they’d never return, and plenty haven’t, but many have.

It’s a different city now, much larger and more complex, offering what cities have always provided, a density of potential connections that make things possible that aren’t possible in smaller, simpler environments.

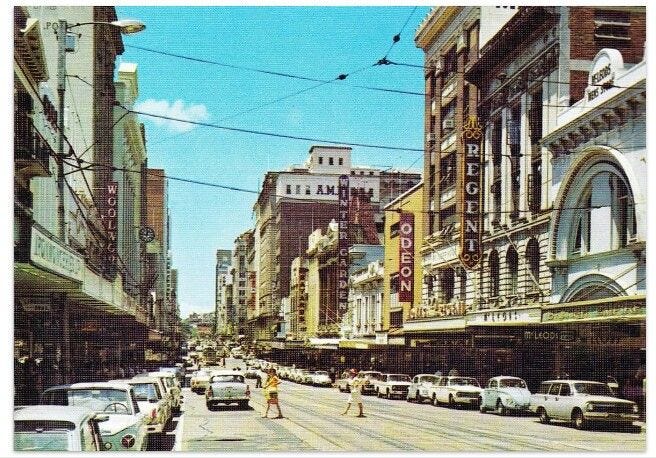

It’s possible to recall the city as a pointillist landscape, a portrait in miniature for sure, but one that captured pretty much all there was to see back then. Here, the bleak squalor of the Valley and its sideshow ally, the clutch of brothels, strip clubs and underground casinos, all of them protected by Sir Joh Bjelke-Petersen’s fantastically corrupt government and police force. There the officially-approved and legitimate vices to be enjoyed in licensed beer barns and a handful of exquisitely terrible nightclubs.

Beer was the signature scent of the streets after dark. Beer gone flat and warm, beer tipped down thick sunburned necks, beer spilled out, or thrown up, or chasing after rum-n-cokes.

You could get a decent coffee if you knew where to look, but most people didn’t. You drank beer; you ate steaks; you wore collared shirts and deck shoes to the Regatta or the R.E. or to Fridays or City Rowers. The city back then seemed to me the type of place where you dressed formally for a business breakfast, but nobody would blink when you combed your moustache dandruff into your complimentary fruit salad. A handful of private schools sent generations of well-fed princelings to a handful of law firms and counting houses to fix themselves upon the city like the teeming sores from AD Hope’s ‘vast parasite robber state’. A handful of finishing schools bred their wives.

Or so it seemed if you did not go to those schools or firms.

They remain, of course, and may still think themselves foundational, essential, and irreplaceable. But time makes fools of us all.

It embarrassed the old regime at the height of its power. In a satisfyingly Hegelian instance of karmic payback, it was one of Sir Joh’s grandest schemes that brought the old world down. Some of the city’s poorest residents and its first peoples were displaced by the vast engineering works needed to transform the southern bank of the river into the site of the World Expo in 1988.

Bjelke-Petersen did not survive in office to open the global fair, driven from power by revelations of corruption which by then was too grotesque and unrepentant to hand wave away. And with him and his henchmen gone, the city changed. Expo was a large part of that, showing that it was possible to move on from how things had always been. Archaic, squalid and crude.

Not all change is for the good, of course. The Brisbane of David Malouf’s writing, of Andrew McGahan’s and even Nick Earls’, the anti-McGahan, is either gone or slipping away. I lived in streets where one slumping wooden shanty after another hid behind thick stands of wild banana trees and runaway jungle vines. These are now bright avenues of renovated Queenslanders or, more often, blank-faced apartment blocks and gated townhouses. You can, of course, get a beer on the weekend without paying elephant bucks for an interstate flight. And hundreds of thousands of refugees from the southern property markets have poured over the Tweed and brought with them demanding expectations of how a city should be.

Milan Kundera reminds us that nostalgia is “the suffering caused by an unappeased yearning to return.” Nostalgia, then, is not entirely appropriate when contemplating the city of the recent past. But neither is amnesia.

top bit of writing. Even the change from my arrival to know is pretty stark. I think for the better, though there are some things I'd really like to see encouraged but no where is perfect

I remember being pulled over by the cops on coronation drive, as a newly minted green P-plater. I was following a flatmate to her mechanic and had to explain to the cops that I was a nervous driver, unused to city driving and if I turned the engine off the car was unlikely to start again. They insisted that I turn off the engine, and then they had to spend the next 40 minutes trying to get the car to roll start. It took a while for me to figure out the push start wasn't working because I still had the hand brake on. My flatmate was stoned off her chops and hid around the corner, rolling around laughing watching the entire scene.